Chords are like actors on a stage

- schoolofmusictheor

- Feb 14, 2022

- 5 min read

Updated: Mar 14, 2025

I am a member of the Curious Piano Teachers, and in November 2020, I was asked to contribute to their monthly "Curiosity Box" about keyboard harmony. I was delighted to contribute to this online community of fellow "curious" piano teachers! I remember waking in the middle of the night one night that November, and because I was having trouble getting back to sleep, I decided to scroll through Instagram. Not the best solution for insomnia, but perhaps very human in the 21st century. And while I was scrolling, I came across this:

"Chords are like actors on a stage; they all have a role." Lona Kozik

In my bleary-eyed, either-way-too-late-or-way-too-early haze, I wondered if I was having a lucid dream! Then I remembered that I was contributing a keyboard harmony course to the CPT curiosity box for that month, and this must have been something I said on our Friday live Zoom call. I don’t remember saying it, but it turns out it’s true!

And here’s why.

All notes are not created equal

All notes are not created equal, at least not in diatonic tonality.

By diatonic, I mean "the major and minor (scales), made up of tones and semitones...as distinct from the chromatic, made up entirely of semitones." (Oxford Dictionary of Music)

By tonality, I mean "loyalty to a tonic" (ODoM); that is, music that is in a key and has a home note (the tonic).

When I think of diatonic tonality, I think of classical music (small C) encompassing the Baroque (1600-1750), Classical (1750-1820) and Romantic (1820-1900) styles. In the diatonic system of tonal harmony that grew up in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, all notes are not created equal. This blog post will focus on the notes of the major scale.

Imagine a major scale as an ecosystem

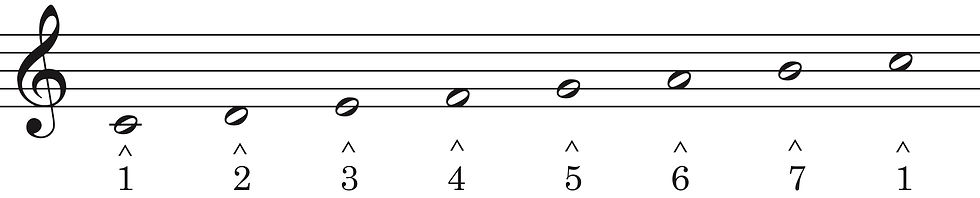

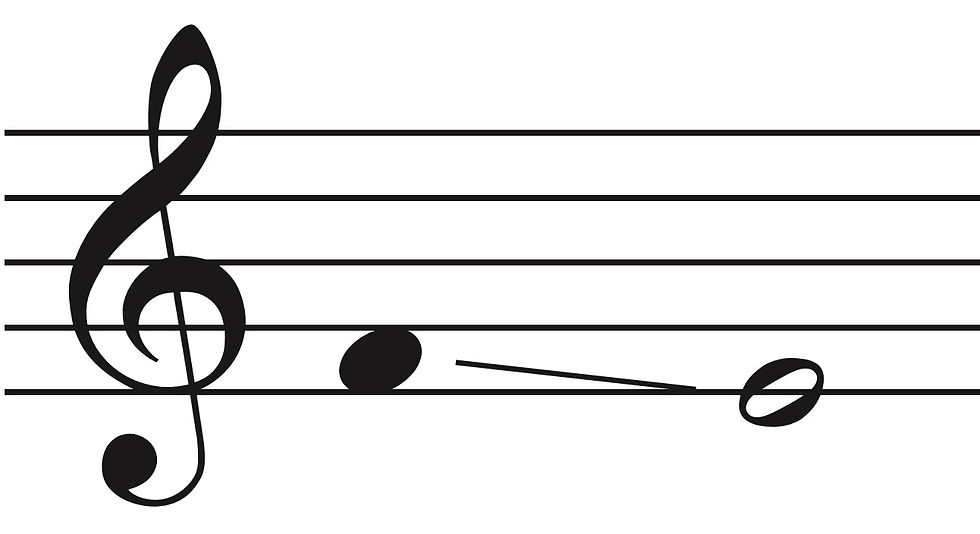

Imagine a major scale as an ecosystem. Let's look at C major. Each tone of the C major scale gets a number and a name:

C is the home note - called the tonic - from which this scale is built and to which it returns at the top of the scale. It is the most stable note of the scale, because it is the home note. It doesn't need to go anywhere. In fact, it is what we are constantly headed toward when we leave it.

If we build a chord on C (chord I), the notes of the chord are also stable, especially when sounding together.

As part of the tonic triad, E is pretty stable in the ecosystem of the C major scale. It harmonises the tonic, and it doesn't need to go anywhere.

Following on from last week's post about the consonance of perfect 5ths (you can read about that here), G (scale degree 5) might logically be the second most stable note in the C major scale. When heard within the context of a I chord, this is true. But heard on its own, it is dynamic and often implies a return to scale degree 1 (C). So it has a dual function the major scale. It can be both settled and dynamic, depending on context.

Scale degrees 1, 3 and 5 (5 when taken with 1 and 3) are stable and don't need to move anywhere. The notes of the rest of the scale are more or less dynamic and have tendencies to move toward one of the more stable tones. Let's take each tone in order of least dynamic to most dynamic.

Tendency Tones - Whole Tone Relations

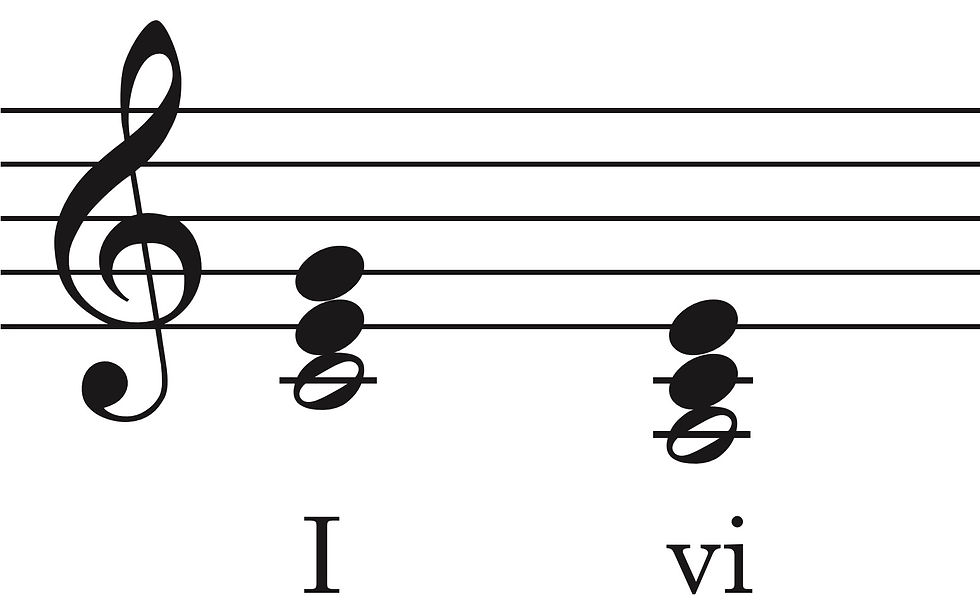

A (scale degree 6) has a variable role. On the one hand, it is the note of the relative minor scale, and so in this respect, it could be seen as a stable part of the key structure.

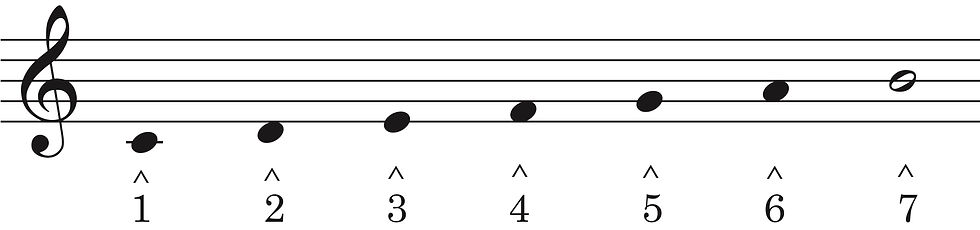

But taken as part of a different harmony, like the chord built on scale degree 4, for example -

- scale degree 6 has a tendency to resolve down by step to the more stable scale degree 5.

In a similar fashion, scale degree 2 (D) has a tendency to move up to the more stable E or down to the most stable C.

In both cases, the relation of this tendency tone to nearby stable tones is a whole tone.

Tendency Tones - Semitone Relations

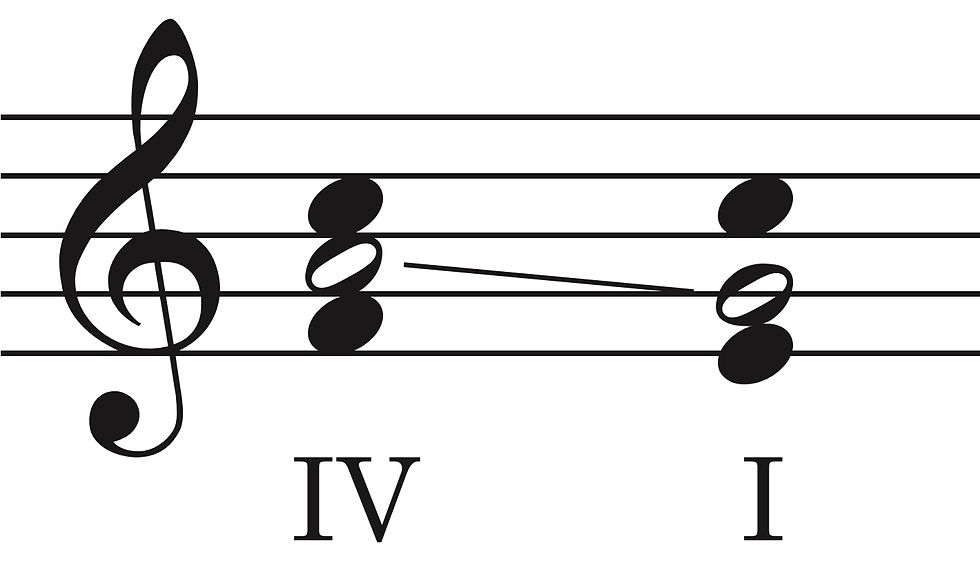

The most dynamic tendency tones in a major scale have semitone relations to nearby stable tones. Scale degree 4 (F) is next to both scale degrees 3 and 5, both stable (when taken together as part of a I chord), so potentially, it could move to either note. But the strongest pull is to move down by semitone to scale degree 3.

Semitones present dynamic relations that fuel the impetus from dominant to tonic in the diatonic tonal system. And scale degree 7 is perhaps the most dynamic.

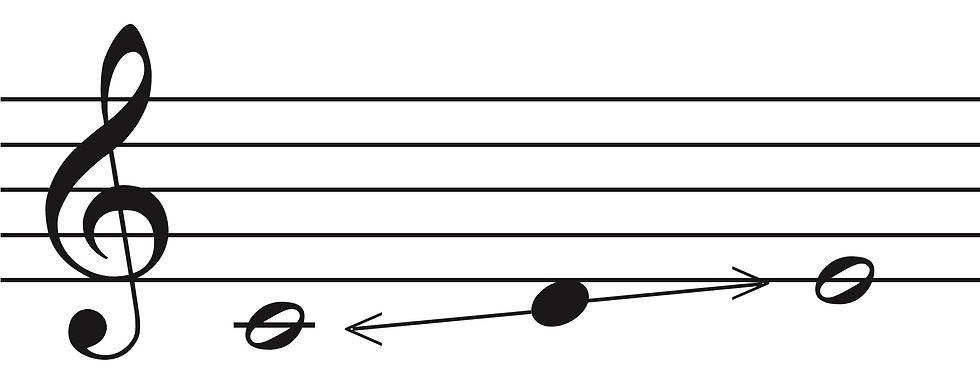

Let's do a little listening experiment. Play or sing a major scale going up, but stop on scale degree 7.

How does this feel? Does it give you any physical sensation in your body? Can you hear what should happen next? Can you sing the note that should follow scale degree 7?

Within the context of classical music, scale degree 7 urgently wants to step up to scale degree 1.

In fact, scale degree 7 gets the name "leading note" or "leading tone" to illustrate the function of this note within the ecosystem of the major scale. Scale degree 7 (B) leads us back to the tonic (C). It is this underlying impetus to resolution that gives the dominant chord its dynamic role in the major/minor system. The leading note is the subtext to the role the dominant plays in diatonic tonality.

The Tonic-Dominant Axis

The leading note is an important feature in the dominant triad of any major or minor key.

The dominant triad is built on scale degree 5 (G in the key of C major).

Notice that B is the third of the G chord. So built in to this harmony is the impetus to resolve to the tonic (C).

The leading note, B, has a semitone pull tothe tonic, C. In this context, G has a dynamic pull to C (scale degree 5 to scale degree 1 - movement by 5th which we often find in the bass).

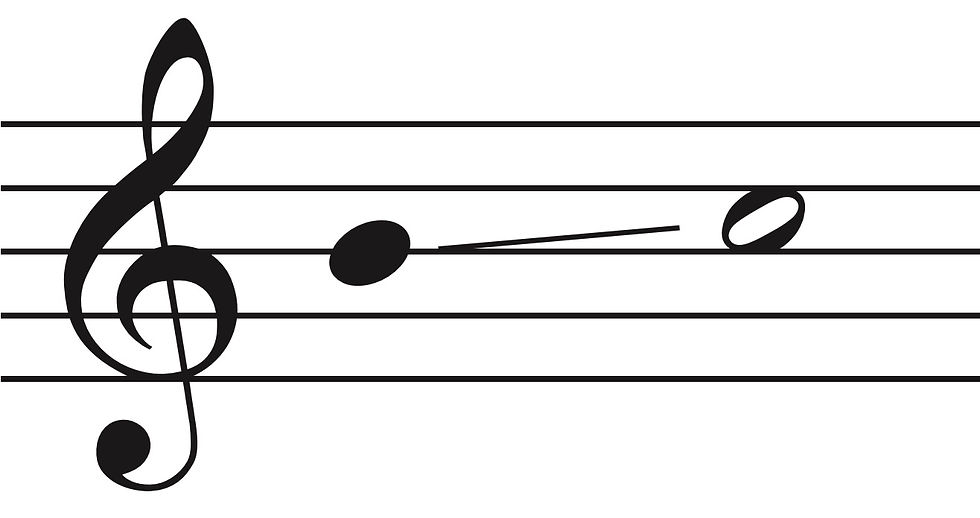

When you add the 7th of the V chord, the need for resolution becomes even stronger. The 7th of the chord is scale degree 4 (F) -

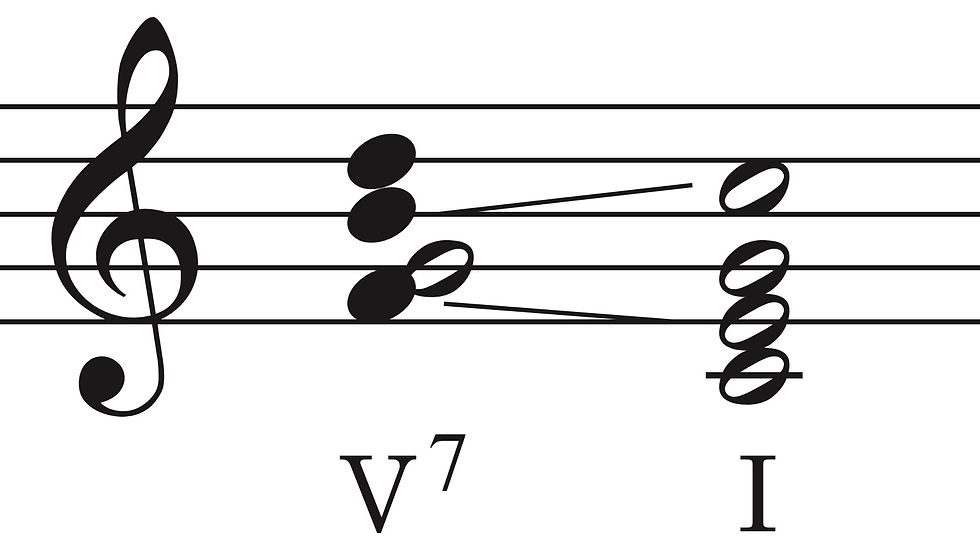

- and remember that scale degree 4 (F) is the other tendency tone that has a semitone relation to scale degree 3 (E). So a V7 chord has two tendency tones that have strong semitone pulls to nearby stable tones. Notice that they move in opposite direction. This contrary motion also makes for a strong resolution.

Scale degrees 4 (F) and 7 (B) also happen to form a tritone:

The tritone is a dissonant interval that encompasses three whole tones (F-G; G-A; A-B), thus the name. It can be represented as an augmented 4th, as it is here, or as a diminished 5th:

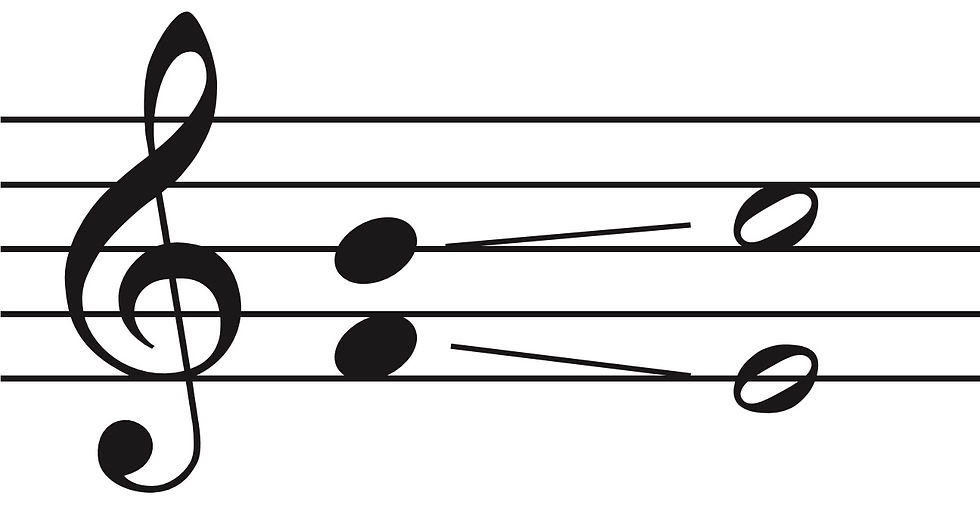

Either way, the tritone must resolve doubly by semitone within the context of a major scale. The augmented 4th resolves outwards -

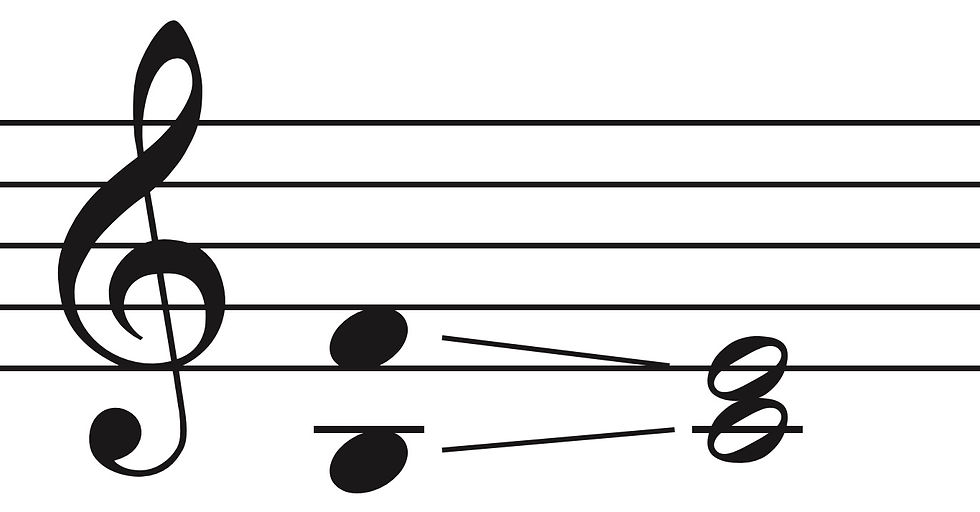

and the diminished 5th resolves inwards -

Taken together with motion by 5th (scale degree 5 to scale degree 1) in the bass, this resolution articulates the Tonic-Dominant Axis that defines every major key around the circle of fifths.

Conclusion

The rest of the chords built from notes of the major scale have particular functions along this Tonic-Dominant Axis. They all work together in their particular roles, like actors on the stage, with the sole purpose to ultimately drive back to the home note and home chord, the tonic. The development of harmony, both diatonic and chromatic, along this axis defined the work of composers for 300 years.

Comments